Legibility and Democracy

I. The Importance of Legibility

Legibility in the context I am using it here refers fundamentally to the understandability of a system.

It might seem obvious that more understandability is better, but understandability also implies simplicity, and simplicity is not necessarily always good. For example, with governmental policy, as addressed in James C. Scott’s book “Seeing Like a State” (archive), a drive for legibility can result in adverse situations such as city planners neglecting important complexities that are necessary for a healthy society, or agricultural reforms that promote monocultures and deplete the soil. This idea of legibility can be applied more widely, to cover any kind of system, process or theory – there is a balance between a theory being legible enough that it can be understood, and being nuanced enough that it gets the correct answers.

Another useful concept to throw into the mix is Philip E. Tetlock’s classification of “Hedgehogs” and “Foxes” (archive). Foxes are defined as people that have many competing ideas, theories and heuristics which they use to navigate the world and make predictions, while Hedgehogs are defined as people with one big idea or theory, which they try to apply to everything. In Tetlock’s work, he finds that Foxes are usually much better at forecasting, tending to make predictions that are more accurate, and being less overconfident in their conclusions. Hedgehogs, on the other hand are found to have extreme overconfidence in their particular theory, despite their predictions often failing to materialise. I intend to be less critical of Hedgehogs however, as I think their approach, whilst not immediately the best approach for forecasting the future, does have its uses.

Combining these two concepts, it is probably not too much of a stretch to describe Hedgehogs as seeking legibility, and Foxes as being comfortable with illegibility. As a Fox, if you have many theories, how do you know which one to apply? Even if your heuristics work very well to predict the world, it is difficult to explain them to someone else, therefore illegible. On the flip side, as a Hedgehog, you can explain your thinking very easily, making it legible – you apply your theory, and it generates a prediction. Your ability to predict things however, is entirely dependent on the strength of your theory, which may not have enough depth to fully capture all of the nuances of reality.

In some ways, the collection of heuristics that Foxes use is analogous to culture and tradition referred to by Joseph Henrich in “The Secret of Our Success” (archive). The heuristics promoted by a culture can be very powerful, but without them being legible, they are hard to justify to outsiders. Asking ordinary people in a tropical country “What is the point in ritually washing this vegetable before cooking with it?” is unlikely to get you an answer like this. This can also be seen as a justification for the precautionary principle of Chesterton’s Fence – just because a heuristic, process or structure is not legible doesn’t make it useless.

In a world of only extreme Foxes, we would be able to make reasonable predictions about things, but explaining why we think what we think would be difficult, in much the same way that explaining why exactly the weights on the nodes of a neural net allow it to recognise text correctly is a virtually impossible task. A world of only extreme Hedgehogs on the other hand, would have a selection of understandable theories and methodologies for approaching the world, which would likely be applied with confidence, followed by catastrophe as reality collided with the overly simplistic approach, just like High Modernism.

I think it is fair to say that both science and society work best somewhere in the middle, with a mixture of both approaches. A less extreme Fox might be happy using different maps for different purposes, but be slowly trying to iron out areas where they contradict, just as a less extreme Hedgehog might prefer to use one map for all purposes, but be slowly trying to incorporate other details into this map that are missing but useful. Fox thinking may be much better for predictive purposes, but Hedgehog thinking is clearly more focused on trying to combine theories into a cohesive whole, which is a valuable project for increasing legibility. As you may be able to tell from the multitude of links to Scott Alexander’s blog above, this is a theme that he has written extensively about (archive).

II. Finding a Balance

When trying to systematise the world, it is to be expected that any theory will get worse before it gets better. First we have a set of illegible heuristics that work quite well, then we try to come up with a theory that is legible instead. This legible theory does a worse job of modelling the world than the heuristics did, but some Hedgehogs use the theory anyway. These people inevitably fail, but through their failures demonstrate where the theory needs improvement, adding complexity to the theory, but resulting in slow incremental gains to the accuracy of the system.

Eventually, we might end up with a theory that works as well as (or even possibly better than) the heuristics we started with, but this takes a lot of time, and a lot of heroic failure on behalf of Hedgehogs. A theory develops over time until it incorporates enough complexity to be acceptably accurate, but it is no good noting that a theory does an inadequate job, and condemning the idea of seeking theories entirely. While a failure mode of Hedgehogs is being overconfident in an insufficiently comprehensive theory, or refusing to update a theory that has proved inadequate, a failure mode of Foxes is not even trying to find a model for something, or not caring about an obvious contradiction between different heuristics.

This suggests finding a balance between legibility on one side, and accuracy and effectiveness on the other – a sweet-spot where people can understand what is going on well enough to do what they need to, but also be sufficiently accurate. As theories and systems become more complicated, they risk slipping back into illegibility once more, at least for non-specialists. Most people could get to grips with Newtonian Mechanics, but very few can become fully comfortable with General Relativity. In this sense, although General Relativity has made black holes and curved spacetime legible to some physicists, it is effectively an illegible heuristic to most people. Newtonian Mechanics is more legible, and is acceptably accurate for most scenarios, even though in theory General Relativity is a better model.

The same concept applies to systems such as a legal code – laws are usually legible to lawyers, but are sufficiently complex that ordinary people view the legal system as a black box handing out judgements. A legal system that is too simple would not work for anyone, as there are too many edge cases that must be considered. The tendency of laws to be written in “legalese”, renders them effectively in a different language, despite the fact that this makes them much more robust.

Just as someone using Newtonian Mechanics could hire a physicist when they get too near a black hole, if there were a more universally legible version of a legal code, this would better enable people to interact with the law, whilst still allowing them to hire a lawyer if they got too near an edge case, providing a sweet-spot of both legibility and effectiveness. In fact, having a parallel document to the law itself, consisting of non-legalese, straightforward descriptions of the laws listed, would make for an excellent addition to the current legal system in many countries. This could be entirely subordinate to the law as written in legalese, so there would be no ambiguity if it was unclear, but it would simply give ordinary people the ability to understand in broad strokes the laws which apply to them.

Of course, in the UK, the law is already unusually illegible anyway – a combination of statute law, common law and case law, some of which is not even publicly accessible. Add to this multiple layers of amendments of the form “replace paragraph 2 subsection 3 with the following text…”, which are often not actually incorporated into the main document (this would require a separate act of parliament). Clearly UK law is in dire need of being made more legible to lawyers themselves, before mere mortals stand a chance at getting a non-legalese version.

III. Legibility in a Democracy

If we apply this principle to democracy, we can get some interesting insight. A highly centralised democracy is very legible – people vote for the leader, who appoints whatever officials they require. Very simple and understandable. Firstly however, this centralisation brings with it the downside of inflexibility – if different areas need different treatment, the leader needs to fully understand all the issues to be able to treat them correctly. Without this understanding, they may attempt a “one size fits all” approach which causes unnecessary inefficiency and strife. Even aside from the downside of inflexibility that centralisation brings, this simplicity makes it fundamentally not very democratic – you are effectively periodically electing a dictator, and with so much concentrated power, it is quite possible that one of these temporary dictators finds a way to make it more permanent.

Another very legible democracy is one where every decision and law is put to a plebiscite based on a simple majority. Again, aside from the enormous inefficiency of this system, it is similarly not actually very democratic – without any mechanisms for compromise, consensus building or minority protection, this suffers enormously from the problem of tyranny of the majority. A sufficiently polarised society using this system is easily comparable to one consisting of 51 wolves and 49 deer – a vote on whether or not to eat the deer would be easily passed by a majority. Without a robust system of checks and balances, this overly simplistic system can easily turn into a tool of oppression.

Looking at the other end of the spectrum, the UK is a good example of a really quite illegible democracy. Firstly, the executive government is not directly elected, but formed out of a group of local legislative representatives, in an opaque process behind closed doors. This blurs the lines between setting the laws and running the country, and sometimes makes the decision of who leads the country very unpredictable.

Secondly, local government is dealt with on a hugely inconsistent basis – there are multiple sub-national entities, each with different powers. Scotland has a parliament with a great degree of autonomy, but is still governed in part by the parliament of the UK. Northern Ireland, Wales and London have assemblies with some devolved powers, and some other large cities have directly elected mayors. Powers are split between these entities of varying seniority, and local councils, some of which are the smallest unit of government (Unitary Authorities), and others are split into two levels (County Councils and District Councils) with different responsibilities.

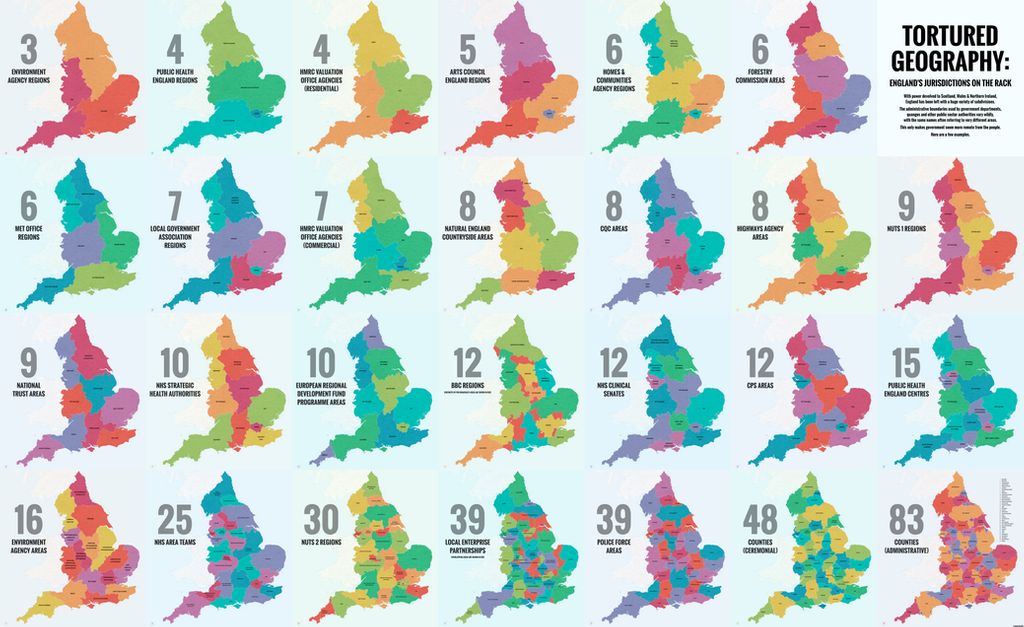

This means that if you live in Kirkcaldy, government functions may be performed by the unitary Fife Council, the Scottish Parliament or the UK Parliament, whereas if you live in Skipton, they may be performed by Craven District Council, North Yorkshire County Council or the UK Parliament. There is no level at which these powers are consistent – even at the very top, there are powers the UK Parliament hands to the Scottish Parliament, but which it keeps for all other areas. To add insult to injury, this is still not the end of it – Post Codes are used for a wide range of purposes, many unrelated to the postal system, but are far from coterminous with county or district boundaries, and counties are grouped together inconsistently for a wide range of administrative purposes, as per this magnificent monstrosity from artist/cartographer Alasdair Gunn:

For anyone to successfully interact with this system, they need specific knowledge of the local structure, which is not necessarily transferable to another jurisdiction.

IV. Federations as a Middle Ground

If we try to find the sweet-spot in the middle, we can consider some other countries – France’s democracy is very centralised, and therefore very legible, but not quite so simplistic as the first example above. There are local representatives as well as an elected president, but unfortunately this still requires the heavy machinery of the central government to get bogged down in the minutiae of far flung and unique environments such as Corsica, Mayotte and Guiana. The effort needed to administer such places is disproportionate to their population, causing inefficiencies, but not administering them would be neglectful, leading to its own problems.

Alternatively, we can look at the US – a federation. Here, we have aspects of illegibility – each state has its own laws, which may differ from its neighbours, but at the same time, each state is treated consistently by the federal government. This means that although people moving between jurisdictions may need to learn multiple sets of rules, there are constants – they are always interacting with the federal government in the same way. It is an ongoing source of disagreement in the US, exactly how much is centrally controlled vs. how much is state controlled, which is often portrayed as a disagreement about the “strength” or “size” of the federal government, but this could easily be portrayed as a disagreement about the overall legibility vs. flexibility of the system.

Zooming in even further, we see even smaller structures – counties and municipalities, which administer certain devolved decisions and services themselves. Again it is a decision to be made how much is devolved, and how consistently. The benefits of flexibility are great, so I am personally inclined to see things devolved as far as is practical, with no government function being performed at a higher level than is necessary to facilitate sufficient coordination, however this must be balanced against the need for a certain bare minimum level of legibility at each level of government.

Even if at each level of government, the level below is able to have variable rules and approaches, the relationship between the units and subunits of government should be kept as consistent as possible, to leave the structure of government legible. One US state may be split into “counties”, to which certain powers are devolved, and another into “townships”, to which different powers are devolved, but each state has the same powers devolved to it by the federal government, and each subunit has the same powers devolved to it by the state. Having both “counties” and “townships” as first-level subunits of the same state would be a recipe for confusion, as it is with Unitary Authorities, Counties and Combined Authorities in the UK.

To have a populace that is democratically engaged, a certain amount of legibility is critical. Politicians should make it easy for people to interact with their government, which means giving them minimal sets of rules to learn, and making it easily understandable which level of government they need to interact with for different purposes. If people live in one area and work in another, they may cross a state or county line, therefore having to interact with two separate jurisdictions with different rules, but if the structure of government is consistent, they can at the very least know what they do not know.

Clearly, if states are too small, people may need to interact with more than two different states, which again becomes unwieldy (for example, 7 Swiss cantons have both a population less than 100,000 and an area less than 1000 square kilometers). Unlike smaller units such as counties, which tend to have mostly administrative powers, states can have a huge amount devolved to them including taxation and writing laws, allowing for significant differences which must be learned. In a federal system therefore, finding both the right sizes for states, and the right powers to devolve to them is very important to ensure that the populace has the right balance of flexibility and legibility to remain democratically engaged.

V. Legible for Whom?

Another attempt at balancing the need for legibility with the need for effectiveness is technocracy. This approach has highly specialised people, to whom more complex systems are able to be legible, with the hope that they can come up with “the best solution”. This becomes difficult for the public to understand however, which then conflicts with the ideals of democracy. Singapore’s approach here was to take unpopular but necessary actions that were so successful that people were won around to them before they turned against the government.

This has worked for Singapore, but is not necessarily a guaranteed approach for several reasons. Firstly, even if a country is careful not to predominantly recruit technocrats from more economically advantaged groups in society, they are still likely to diverge culturally from the rest of the populace over time, becoming out of touch, less representative, and optimising for the wrong things. Secondly, it is possible for technocrats to become overconfident in their theories and abilities, due to “echo chamber” like effects, allowing for mistakes similar to High Modernism. Finally, the greater the impact of a policy and the more uncertainty there is around which approach is best, the more it is worth testing before full country-wide implementation – this would slow the process down, giving more time for opposition to form, which either results in beneficial policies never being implemented, or in the government implementing things without testing with negative consequences. E. Glen Weyl writes further on the problems with technocracy, but needless to say, for all the potential benefits of a technocracy, if people don’t understand what is going on, it cannot be very democratic.

Whilst legibility supports public engagement, too much legibility allows demagogues to offer easy solutions. Simplifying things to cater to the lowest common denominator (a busy person with no time to spend understanding the nuances of policy) doesn’t allow for informed debate either. It is desirable to strike a balance between legibility and effectiveness. For this, you need people with enough time to invest in understanding the issues, whilst still being representative of the populace as a whole – not a political class (susceptible to populism, looking for easy answers), or a technocratic class (susceptible to overconfidence, lacking the insight from ordinary people).

VI. Sortition as a Solution

One potential solution to this balance is sortition – the way representatives used to be selected in ancient Athens. This is a process similar to that used for jury duty, in which a number of members of the public who are citizens in good standing are selected at random to perform their civic duty. Using sortition to select democratic representatives avoids the rat-race of election or re-election, reducing the pressure to pander to populism. Its advantages are not simply limited to this however – the representatives being randomly selected from the population all but ensures that the majority of representatives are ordinary people, very much in touch with the wants and needs of the average citizen, rather than out of touch career politicians or technocrats. Furthermore, given a large enough random selection, it can be made highly statistically likely that the selected people are a good representation of the population at large, which makes it likely that all interest groups are being represented.

It could be argued that since ordinary people do not tend to take the time to understand the nuances of policy normally, this would be a disaster. However in the case of jury duty it is usual for people to take this civic duty very seriously, and when given leave from their job to perform this function, they have the time to look into any nuances in order to better understand them and make informed decisions. In fact, there are studies suggesting that politicians that are more open minded and receptive to new perspectives may be less successful at being elected, which may mean that the amount of nuance that politicians are likely to be able to understand is less than that of the average person.

When preparing for the Marriage Equality referendum in the Republic of Ireland, the government made heavy use of focus groups that were representative of the population at large. This was in order to ensure that they understood the concerns of every different demographic, to allow them to put across the proposed constitutional amendment in a way that wouldn’t alienate large groups of people. In comparison to a previous referendum that failed, this article states:

The main thing that emerged… was that voters had a range of fears that they never got a chance to articulate.

By ensuring that ordinary people from all walks of life are included in the process of governing and lawmaking, sortition could dramatically reduce both the issue and the perception of politicians being out of touch.

In short, legibility is a desirable quality for any democracy, because for the public to be able to decide how they should be governed, they must first understand how they are governed. Seemingly in opposition to this however, are demands for effectiveness and resistance to exploitation, which are also fundamentally necessary for any stable democratic system of governance. Federalism and sortition seem to be very promising candidates for mechanisms that (if implemented in the right ways) could satisfy both sides of this trade-off, allowing for a large amount of legibility whilst still being flexible, efficient and difficult to exploit.

9 Replies to “Legibility and Democracy”

> One US state may be split into “counties”, to which certain powers are devolved, and another into “townships”, to which different powers are devolved, but each state has the same powers devolved to it by the federal government, and each subunit has the same powers devolved to it by the state. Having both “counties” and “townships” as first-level subunits of the same state would be a recipe for confusion, as it is with Unitary Authorities, Counties and Combined Authorities in the UK.

Sorry for being nitpicky, but local governance in the United States is nowhere as streamlined as you seem to imagine it to be. I would argue that the UK system if far more legible.

Generally states will have up to three levels of *general* local government called:

1. Counties (Called Boroughs in Alaska and Parishes in Louisiana)

2. Intermediate Level: Towns/Township

3. Municipalities: Cities/Towns/Townships/Villages

Note that in some states “town/township” is the intermediate level while in others it is the municipal level. Many states only have two levels having abolished or never had an intermediate level. Some of the New England states are so small they have abolished county governments, only having them as geographic labels, and functionally have only the municipal level.

First, we have consolidated municipalities-counties, much like combined authorities in the UK. For example, San Francisco is a city-county and New York City is made up of 5 counties! However, these are relatively rare. There’s only about two dozen consolidated city-counties (and most of these are only partially consolidated) in the US compared to over 50 unitary authorities in England.

Second, we have the issue of unincorporated territory which does not exist in the UK. While every state has all of its territory divided into counties, many states only divide some of the entire territory into the intermediate and municipal levels. For example in California (which only has counties and municipalities) Mr. A can live in the City of Los Angeles which is in Los Angeles County while Mr. B a few miles away lives in Unincorporated Los Angeles County. The County provides some services to all residents regardless if they live in a city or unincorporated area (for example courts and indigent health care), while other services are provided by the County only to people who live in the unincorporated area (for example policing and road maintenance) while the City is responsible for those services in incorporated areas. Both individuals have the same vote for the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, while only the resident of the City of Los Angeles votes for the Los Angeles City Council. The same may occur in a state that has all three levels. For example in New York State, the entirety of the territory is divided into counties and intermediate-level towns, but some areas are also in municipal-level cities/villages while others are not.

Third, in some states the powers and responsibilities that an intermediate- or municipal-level local government has vis-a-vis the other levels will vary based on its charter. For example, in New York State a village has fewer responsibilities and powers than a city even though they fall at the same level.

Fourth, even within the same state the same type of local government may not have the same governance strucutre of elected officials. Some have have a council-manager system where the chief executive is a professional manager is appointed by the elected council. Others have a council-mayor/executive system where the council and mayor/executive are separately elected with vetoes over each other. There are of course hybrids and variations of both types. It is also common for local governments to elect additional officers such as the clerk, treasurer, assessor, controller, tax collector, recorder of wills, superintendent of schools, sherriff, public prosecutor, and coroner. Which additional officers are elected by which local government can vary within the same state.

Fifth, we have special districts which are single purpose governments with elected boards ranging from school districts (the most common type) to fire districts, police districts, health districts, bus districts, regional rail districts, water districts, air quality districts, cemetery districts, library districts, waste management districts, electricity districts, flood control districts, irrigation districts, and so on. The closest thing I can think of in the UK is the elected police and crime commissioner for each police area. Depending on the type, the entire state might be divided into special districts of that type (common for school districts) while other types only exist in some areas. Many special districts provide services that could otherwise be provided by a county or municipality in another community in the same state. For example you might get your fire protection services from the county, a city, or a special district depending on where you live in the same state. In California, which heavily relies on special districts, there are 50 types of special districts and over 4,000 individual districts compared to about 500 municipalities (here is a [fun map](https://mydashgis.com/CSDA/map) of all of the non-school ones).

Sixth, we have out of control municipal fragmentation in many states where the boundaries of local governments are historical artifacts that have no relation to the current community geographies and economies of where people live and work. This is Los Angeles from [space](https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=PIA02679) while this is a [map of the 88 separate cities](http://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/lac/1043452_BasicColorMap.pdf) which govern the area. Municipal fragmentation is prevalent because many states require that any boundary changes be approved by a referendum of the affected areas. Local politicians are reluctant to give up power so they campaign against mergers, and residents of wealthier neighborhood will oppose joining a bigger city so their tax revenue does not go to subsidize the central city. The same thing applies with special districts, which just adds several more layers to the fragmentation. This does not seem to be a major issue in the UK, since the national government seems to re-rationalize the boundaries every few decades.

Lastly, we have metropolitan or regional authorities (frequently called “councils of government”) similar to the combined authorities in the UK. These are also relatively rare. Not every state has them, and in the states that do only some areas are covered. Even within the same state, each of the regional authorities frequently doesn’t even operate under the same legal framework! The regional authority in one part of the same state may have actual powers and directly elected members while in another part it’s just an advisory body with delegates from the constituent counties/cities.

Not nitpicky at all – I appreciate the thorough run-down. I was aware of several aspects of this previously, but it is a very useful summary of the situation that you have to deal with in the US.

I wasn’t really trying to hold the US system of local government up as a paradigm of virtue, so much as just to find an example of something that could be contrasted against the UK’s system. Clearly by glossing over the complexity of US local government, this has somewhat hindered achieving that goal.

Based on your breakdown, I think I agree that the UK’s system of local government is clearer and more legible, though the improvements that could be made to the UK still stand. Unitary Authorities in the UK are probably comparable to US consolidated municipality-counties, while two-tier counties are similar to US counties containing multiple municipalities.

It is not obvious to me why state governments in the US are not able to “tidy up” local government in the way that the UK has (even though I think the UK could do more). I can see that in a federation, this should be a state issue rather than a federal one, but it seems like it should be within the states’ power to remedy. I could imagine that it is just politics that makes such things impossible in such a divided political system, but if there were any legal reason that a state government that was so inclined could not do this, I would argue that this would be an undesirable restriction.

Ultimately, I don’t think it changes the argument that I was trying to make, but it probably does make it an even more frustrating issue for the US than it is in the UK.

“It is not obvious to me why state governments in the US are not able to “tidy up” local government in the way that the UK has (even though I think the UK could do more). I can see that in a federation, this should be a state issue rather than a federal one, but it seems like it should be within the states’ power to remedy. I could imagine that it is just politics that makes such things impossible in such a divided political system, but if there were any legal reason that a state government that was so inclined could not do this, I would argue that this would be an undesirable restriction.”

Many states are influenced by the state constitutional theory of “municipal home rule” in which local governments are recognized to have an inherent authority emanating from the people rather than being mere creations of the state government. In this constitutional framework, both the state government and local governments are seen as creatures of the state constitution, with seperated powers, which can only be amended by a higher constitutional power (usually a vote of the people or a constituional assembly). State governments do retain varying abilities to regulate municipalities when there is a strong interest in having statewide uniformity. Although only 19 states have officially recognized this theory, (including many of the more populous states), it likely has an influence on politics in other states. Additionally, many states have state constituional requirements for changes in municipal boundaries to be approved by the voters of the affected areas. As discussed in my previous comment, this often leads to self-interested refusal by subareas to combine into more organic agglomerations for the better of the whole area.

Politically, a state government interfering in local government affairs is seen as upsetting the natural order of things. Americans have a general distrust in government which I believe grows with each level. So, Americans are more likely to side with their local government in a political dispute with their state government. Additionally, state legislators are often former municipal council members (and the political machines which elect them are often tied up in local government) making them unlikely to support changes opposed by their former municipal colleagues.

You are correct that the national federal government has almost no involvement in municipal formation/boundaries, leading to a seperate system in each of the states.

My takeaway is that in any federal or quasi-federal system (if we think of home rule municipalities as having a quasi-federal relationship with their state governments) it is important to have a regular process with strong constituional mandate to rebalance the constituent units. Or else population changes will eventually lead to arbitrary political boundaries and imbalances which undermine the functioning of a federal system. I think that it’s unlikely that the constituent units, through their governments or through referendums, will on their own resolve these issues in a way that is beneficial to the whole.

This makes a lot of sense.

“it is important to have a regular process with strong constituional mandate to rebalance the constituent units”

I couldn’t agree more!